The Tailor and the Tech Stack

FM (Friday Morning) Reflection #43

Odds are you missed Bossa Nova, a rom-com film from the year 2000 directed by Bruno Barreto. Set in Rio de Janeiro, it’s a love letter to the city and the music of Antonio Carlos Jobim. While I only vaguely remember the details of the plot, there is a minor character in that picture who made an impression on me that I remember vividly to this day.

He’s a master tailor, played by the late Argentine actor Alberto de Mendoza, who has a seemingly peculiar, ritualistic practice. When he encounters a bolt of fabric, he approaches it with profound respect. He looks it over. He examines and feels its texture. Then, he leans in, puts his ear to the cloth, and holds it there, listening intensely.

When asked why, he explains that the fabric knows what it wants to be. It has an inherent calling woven into the threads. The tailor’s job isn’t to force his will upon the cloth, but to listen closely enough to hear the cloth tell him what it wants to become. His job, as the tailor, is simply to help bring that into existence.

Feeling the Grain

I think artists who work with physical media understand this process intuitively. While I’m not a sculptor or painter, I am a photographer, and I know what that feels like. You position yourself, you wait, and you practice patience, sensing what might happen before it actually does. You aren’t directing the scene in any way; you are making yourself available to receive it. I wrote about this in Being ready for the magic moment when everything clicks, where preparation meets the inherent nature of the moment.

I believe there is something similar that applies to the digital, intangible world of data, technology, and systems.

In my line of work—technology transformation, AI, and business strategy—we are constantly trying to bring ideas to life. We want to shape the data, design the architecture, and drive the outcome that the business needs. But I’ve found that databases, networks, and systems have an interior life, too. They have patterns. They have a direction they naturally want to go. And they definitely know what makes them unhappy.

Maybe I’m anthropomorphizing here, but people name their cars and boats, treating them as beings with distinct personalities. This comes from a deep familiarity with their patterns and behavior. Our work, our safety, and even our self-image get wrapped up in these machines because we have taken the time to understand their character. A captain knows exactly how their boat behaves on a choppy sea; a driver knows the protest of their vehicle on a cold morning.

Sensing the Drape

I think anyone who works with technology has felt this same dynamic with software and systems. We all know when a piece of equipment is being “cranky.” We’ve encountered code that is “elegant,” and poor design experiences that come across as “hostile.”

My life partner sometimes calls me her “tech support,” because I seem to have a relationship with technology that is different from hers. When things aren’t working for her, I’ll walk into the room and—often without changing anything—things just seem to start to work.

But it’s not magic. It’s just that I have more intuition about how the pieces fit together, and an understanding of how technical systems tend to operate when they are well designed and constructed. And I also know that I’ll get further if I listen to the system rather than just issue commands.

Tracing the Pattern

When we look at the systems we build, we have to remember where they come from. Data is generated by human activity. Systems are designed by human architects. Just as a brand reflects the values of its founders, human-made systems reflect the thinking, biases, and design philosophies of the engineers who built them and the designers who mapped out the way they work.

This means these systems have a kind of “spirit.” They have things they want to tell us. We can see the echoes of others there. They are a reflection of us.

This becomes incredibly important when we look at Generative AI. We know these models aren’t “real” in the sentient sense—they are mathematical predictions based on vast datasets. But they undeniably have a sensibility. They can be helpful, they can be sycophantic, they can be relentlessly optimistic, or they can hallucinate with extreme confidence.

As we move from being consumers of AI to architects of AI-powered systems, we have a profound responsibility. We are shaping that personality. We are deciding whether the system will be rigid or adaptive, cold or empathetic, an honest broker or a swindler.

Developers often think in terms of functions: “I will build a module that does X.” But the master architect asks a different question: “What is this destined to contribute to the world? How should this feel? How should it behave?” In this work, we design interactions. We create the patterns that future users will have to live with and within.

Threading the Needle

If systems have patterns, and these patterns are often reflections of their creators, then we must think about the impact of the things we create. As architects, creators, and artists, we must provide clues that tell a story — breadcrumbs that reveal the spirit of the innovation we lead.

This connects back to what I discussed in Measurement Matters: From Brand Experience to Bottom Line. We have to look beyond the flat metrics and understand the human sentiment and behavior underlying the data that we create, just as much as we focus on the look, feel, and user experience.

If you are a techical product leader, your task is to figure out the spirit of the idea and how to make that manifest in the systems you create. If you are an analyst, your task is to listen to the process and system data until it reveals the truth of human behavior hidden within the numbers.

This is how we elevate what a system provides into a higher form. We move from “making it work” to “telling a story.”

Taking the Measure

How do we put this into practice? How do we start to understand what the fabric of our own work is going to whisper to the world? It requires a shift from trying to control to observing and guiding:

Focus on the friction points. When a project keeps hitting snags, a team keeps burning out, or a model keeps hallucinating on a specific task, stop trying to “fix” it with more force. The friction is a signal. It is the system telling you that you are cutting against the grain. Pause and ask: Why is this hard? What is the natural path here?

Understand and respect the system’s nature. In the age of AI, this is critical. LLMs are more like storytelling machines, not truth engines. If you try to force them to be databases of perfect fact, you will be fighting them forever. Instead, lean into their strengths—synthesis, ideation, transformation. Build with the nature of the tool, not against it.

Trace the lines. Landscape designers and planners create paved paths are suggestions, but the worn grass shows the truth of where people actually want to go. Look at how your teams or customers are actually using your products, not just how you intended them to be used. There’s likely something to be learned there, and that behavior is its own “spirit” of the system manifesting itself. Design to facilitate movement and intentional direction.

The Bespoke Fit

The master tailor in Bossa Nova didn’t see himself as a manufacturer of clothing. He saw himself as one who served by bringing fabric into its fullest form and function.

Whether we are writing code, designing workflows, or training a neural network, we have the same opportunity. We can choose to be taskmasters, attempting to cajole our code and systems into submission. Or we can be true visionaries and architects, willing to quiet our own egos long enough to hear what the work and the universe is asking of us through that work.

When we do that—when we stop shouting commands and start listening to the whisper of potential—we don’t just get better products. We create things that feel inspired, relevant, and are a pleasure to use.

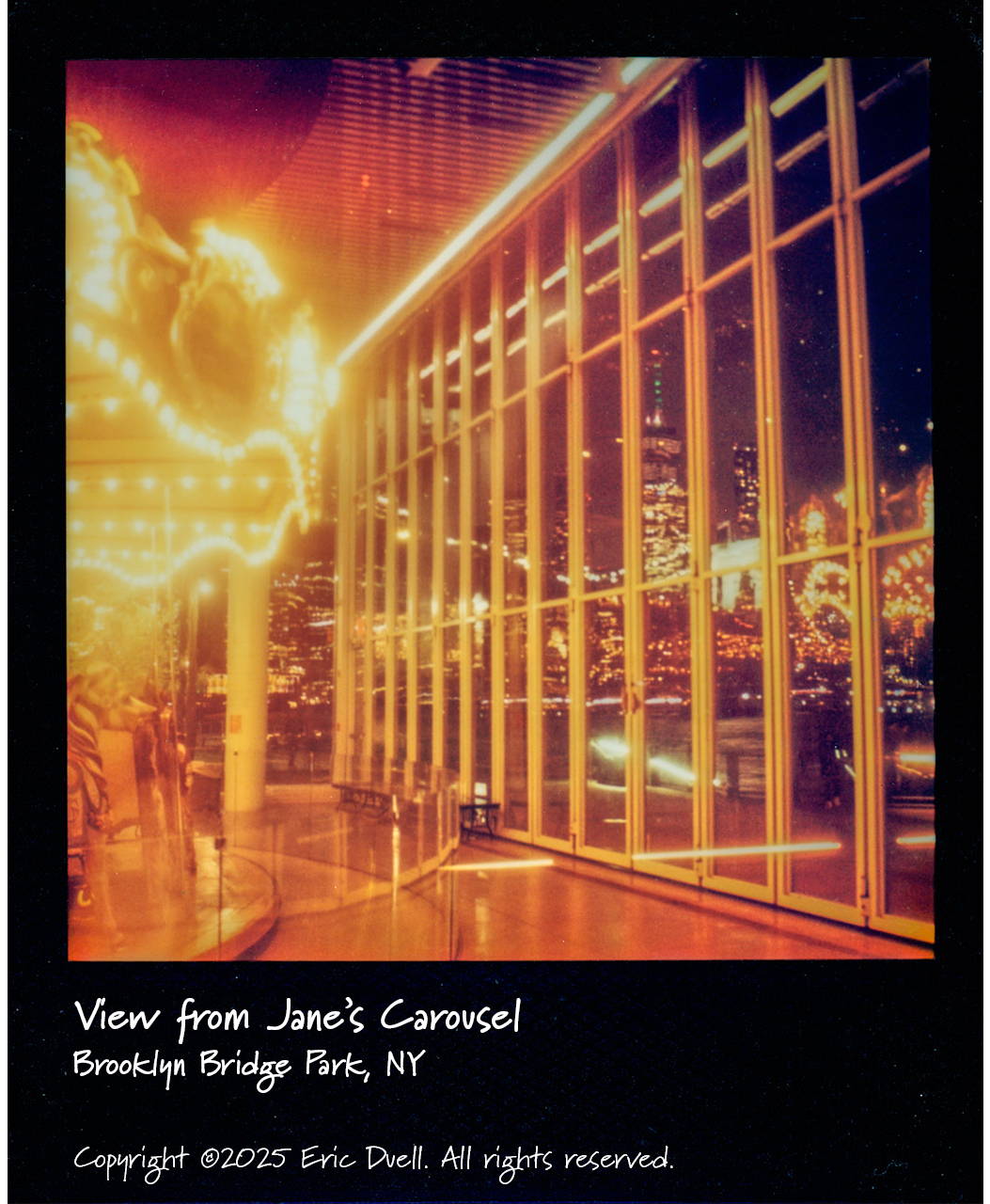

Photo Bonus

A few weeks ago, I stopped by a colleague’s new media production studio in Brooklyn - just a few blocks from the Dumbo waterfront. Walking around, the Manhattan skyline was an obvious take, but the carousel was all lit up from the inside and I walked that direction. Peering inside at the warm glow filling the enclosed space, I looked through to literally a different dimension — the skyline framed up by the windows — and that’s when I realized what this shot should be. Instead of having a fixed idea, I was open to seeing what the situation offered, and this shot is much more interesting because I did.