I find that my writing doesn't always follow a predetermined course. I often begin with a focused topic in mind, but somewhere in the middle—like when I pause to double-check a reference or explore a detail—I learn something new. These discoveries shape the work because researching or verifying a claim forces me to think more clearly and connect ideas I hadn’t previously considered.

It also happens that in the process I spot another jumping-off point and follow that link to learn something new. These detours demand discipline (Friday mornings come fast), but what starts as a cross-check often becomes a fresh inspiration, or occasionally, it triggers a complete rethink. This recursive learning loop—peeling back a layer, making a connection, and refining—is one of the most consistent and rewarding parts of my approach.

In reflecting on this process, I remembered that as a kid, I used to read the encyclopedia a lot. No, we didn’t have the Britannica—it was the Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia, circa 1983 edition, that my mom purchased for my brother and me one volume at a time at our neighborhood grocery store. It was a brilliant marketing strategy for the era: the store would stock the letter “G” one week, and the letter “H” a few weeks later. Each volume was affordably priced, allowing you to build your set piece by piece with your weekly shopping. I still remember the sense of accomplishment when we finally had the full set.

Sometimes when I was bored, I’d pull out one of the volumes and start reading. It might have been something that fifth-grade me was interested in: space exploration, severe weather and tornadoes, volcanoes, or another science topic. Reading about tornadoes might lead me to supercells—the thunderstorms that spawn them—or to radar technology used to spot them.

When I was deeply interested, I’d reread the section over and over. Total nerd, I know—but it meant I could geek out on topics that went beyond whatever was hot on MTV that day. And I often didn’t stop at the end of a topic. I followed where the next page led, and I ended up learning a lot more than I planned. Just like researching for articles I write now, I not only learned about the thing, but the stuff around the thing—or at least adjacent to it in the encyclopedia.

The encyclopedia was a map of the world and facilitated one of the ways I learn: not linearly, but associatively. It’s like going to the grocery store for Gouda and discovering a creamy brie next to it that becomes your new favorite. Or taking a different route home and stumbling upon a pocket park you didn’t know existed.

Curiosity in Practice

That habit—of pulling the thread—never left me. In my first tech consulting job, I was barely a week in when one of our account managers asked, "Do you know SharePoint?" I didn’t. I was handed a thick book and a link to some training materials, and I dove in. The learning curve was steep, but I learned quickly enough to build and deliver a custom solution. More importantly, I was training myself how to learn and adapt in a real-world, high-stakes environment—because my job was on the line.

That experience confirmed something I had sensed as a kid flipping through encyclopedias: if I stay curious and engaged with a puzzle, I can figure things out.

Years later, I knew I needed to understand AI more deeply. That meant starting to learn basic Python. So I bought a few books and dove in. While it was a new language, it built on what I already knew.

A Bias Toward Learning

As I discussed in The AI Skills Gap Is About To Get Real, adapting to a new context starts with a willingness to begin before you feel ready. We don’t always need to change directions entirely. Sometimes, we just need to follow the next thread. And when discovery is its own reward, innovation feels like play.

This perspective shapes how I lead. When I hire, I look for people who are curious, adaptable, and service-oriented. People who’ve worked in roles that required empathy—consulting, account service, advertising, teaching—often bring a knack for learning on the fly. They know how to ask the next question, how to listen for what’s unsaid, how to shift gears without losing the plot. They can sense when something’s off, when a team is out of sync, when a strategy doesn’t align with the context. That’s a skill you can’t fake.

Preparing for What’s Next

This mindset matters more than ever today. We’re standing at a confluence of change—technological, social, and political. AI is reshaping the way we work. Understanding how RAG is used to reduce hallucinations by LLMs, what agents do, and how to deploy new technology are all important things to know in the tech space. But so is exploring the humanities. Art. Music. Philosophy. These disciplines sharpen pattern recognition and support the development of critical and ethical thinking—skills that are essential in the age of AI.

In a world of constant flux, we must look beyond the immediate task at hand to see how things connect. The capacity to intersect ideas across disciplines—and to learn the stuff around the thing—is how we can build a richer understanding of our world. And in a world full of profound change, understanding that stuff around the thing may be just as important as the thing itself.

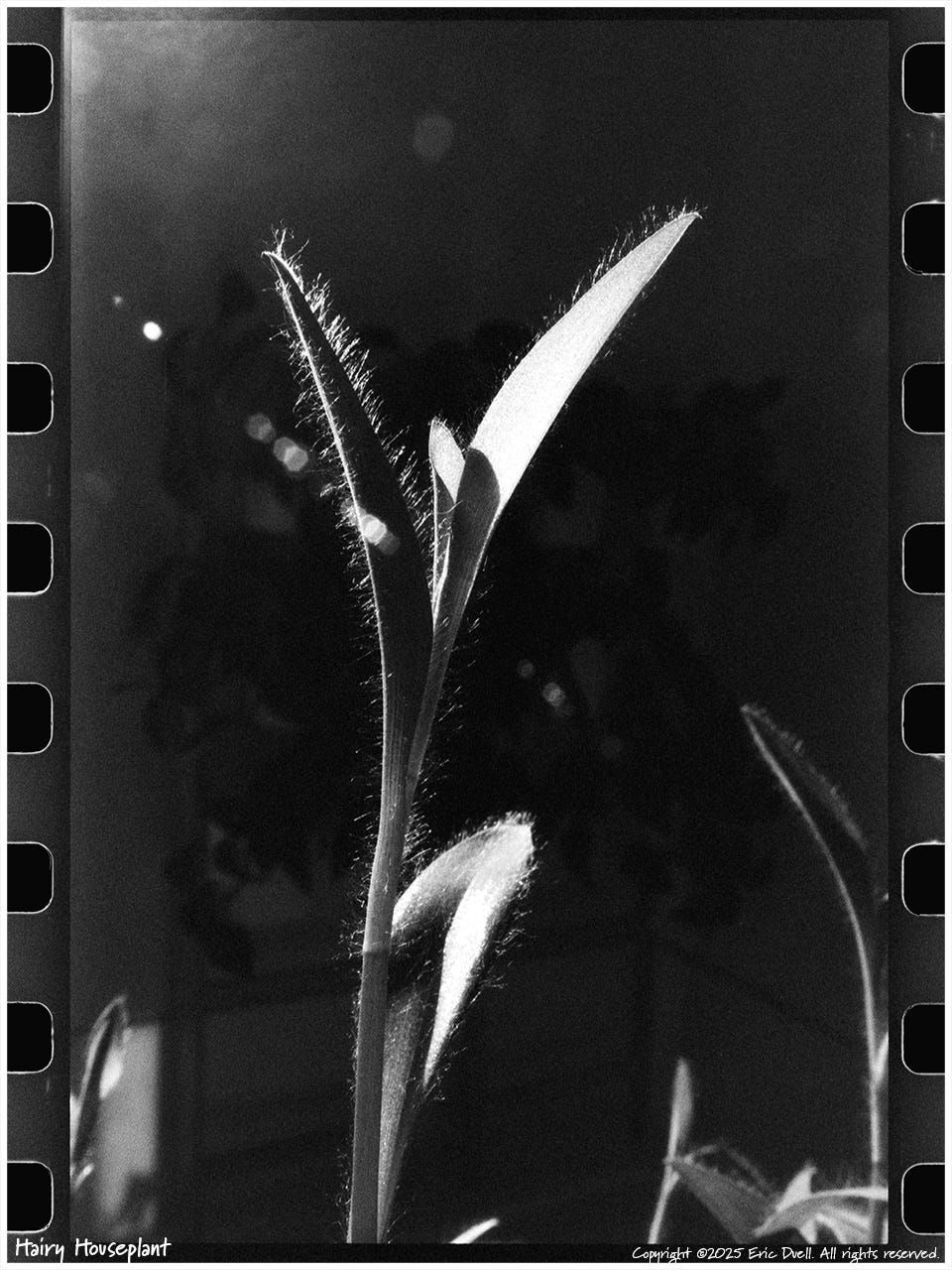

Photo Bonus

In this snapshot from around the house, the sun coming through the window illuminated what makes this photo fun — all the hairs growing from the leaves — the plant version of the stuff around the thing.