Frequently Wrong, But Never In Doubt

FM (Friday Morning) Reflection #44

It’s a quiet, rainy morning in Philadelphia, and as we reach this final reflection of the year, I’ve been thinking back to a moment from this past summer that perfectly captures the spirit of what we’re trying to do here.

I attended my first PolaCon—a conference for the aficionados, practitioners, and creators of all things instant film. It was there that I was introduced to the legacy of Paul Giambarba, Polaroid’s first art director.

Starting in 1958, Giambarba led the evolution of Polaroid’s packaging and visual identity for more than twenty years, and I came to learn about his contributions through a presentation by Giambarba’s son, Andrew, who offered a heartfelt tribute tracing his father’s journey as a cartoonist, illustrator, and designer.

Interestingly, Paul Giambarba was never a traditional corporate employee, despite the massive responsibility of managing Polaroid’s art and production departments. Yet he led the evolution in Polaroid’s packaging, branding, and visual identity to differentiate from other brands on the market, most notably Kodak, to become distinctly recognizable. The rainbow “eye of God” design on Polaroid film packaging and the type-only Polaroid logo? That’s Giambarba’s work.

At the end of the session, attendees were offered posters celebrating his famous Polaroid rainbow design and the revolutionary Polaroid SX-70 camera. At the bottom, in quotes, was a phrase that made me grin: “Frequently wrong, but never in doubt.”

The Double Play

If you read those two phrases separately, you come away with two dramatically different meanings. You have to consider them together, and in that specific order.

To me, the first part is a necessary admission of humility. We often have ideas and notions that simply turn out not to be true. This happens even in the sciences, where “facts” are deemed incontrovertible until we discover a bit more about the universe. If you find a set of encyclopedias from the 1970s or 80s at a garage sale—much like the Funk & Wagnalls set I read as a kid—look up the number of planets or moons around Saturn, you’ll find the “wrong” answer.

The point is that things change. Being “frequently wrong” is just another way of saying we are perpetually in a state of learning. It requires a beginner’s mind and the humility to recognize that our current map of the world is always being redrawn.

We’ve all met people who embody only the second part of the phrase: “never in doubt.” These are the self-assured ones, the entitled, and—too often—those woefully inadequate for the leadership tasks they’ve been trusted with. They frequently misjudge and misunderstand situations, but because they hold positions of power, those around them paper over the cracks to facilitate their “success.”

However, when you anchor that confidence to the first phrase, you get something new — a defining characteristic of advocacy. It’s a conviction that if we follow a rigorous process, bring true competency to our work, and labor tirelessly to deliver, we can move forward with a clear vision that the work is worth doing, even while remaining humbly open to course correction.

The Chef in the Kitchen

A colleague recently made an offhand comment, “I don’t code anymore.” It’s the idea that as you move up, you stop doing and start overseeing.

I gently pushed back on my colleague because I know his talent and that it’s not really true. If I asked him to pull a query from the data warehouse, he’d knock it out in minutes. We’d then have a much richer discussion about how to use that data in the application we were developing.

But it’s not the first time I’ve heard that kind of comment, and when it comes from someone who really doesn’t continue to practice their craft, it strikes me as a recipe for obsolescence.

And the “I don’t do that anymore” statement stuck with me because it highlights a false dichotomy: the idea that you must choose between being a thinker/strategist and being a practitioner. I soundly reject that premise. I’ve seen many who have “arrived” and profess to be experts, but because they stopped being practitioners, they are eventually outmoded by more motivated, curious, and eager employees who still have their imagination and willingness to work hard intact.

Who is the chef that doesn’t go into the kitchen? Is that the definition of an executive chef, or just a manager of a place where they serve food?

While I’ve never considered myself a “true developer” in the professional sense, I am creating platforms and capabilities that deliver business value every day —shipping real products and services that impact earnings. Even if I’m not a developer by trade, I’m building applications with my team and now supercharging that with the assistance of AI.

Modeling the Impossible

This leads me to one of the most transformational roadmaps for leadership that I’ve encountered: The Leadership Challenge by James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner. Central to their framework is the idea of Modeling the Way.

Talk is cheap. You must show and model how you want your team to work, think, and behave. As a leader, you are the most important part of building the culture of your organization. Are you showing how it should be done? Do you know what are you leading toward?

For Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid as well as many optical innovations, the “what” was a technical and human breakthrough. In fact, the very concept of instant photography was born from the seemingly impossible request from a child.

In December 1943, while on vacation in Santa Fe, Land took a photograph of his three-year-old daughter. When she asked, “Why can’t I see them now?” Land didn’t dismiss the question as a childish whim. Instead, he took a walk, and within an hour, the solution flashed before him. He had conceived the camera, the film, and the physical chemistry necessary to make instant photography a reality.

He then spent the next three decades modeling the way as the ultimate practitioner, starting with the commercial release in 1948 of the Land Camera Model 95, the first Polaroid camera.

At the SX-70 launch in 1972, he didn’t just give a speech. He walked onto the stage, pulled a folded camera out of his suit coat pocket, and took five pictures in ten seconds. As the motorized camera ejected the square film and the images developed in broad daylight, he showed the world that he wasn’t just a CEO—he was the master of the “nearly impossible” mechanics and optics he had envisioned. Land was the executive chef who never left the kitchen.

But leading isn’t just about the nearly impossible product; it’s about leading people through the nearly impossible moments of change. I learned this a decade ago when I was thrust into what felt like a real-life reality show competition for my job. The leadership at the time was failing, colleagues were leaving, and the environment was profoundly disorienting.

In that moment of uncertainty, I realized I couldn’t lead effectively if I couldn’t define who I was and what I stood for. I had to do the deeper work of illuminating my own character. I reflected on the leader I would want to work for and landed on the core values that still guide me today: Integrity, Advocacy, Competency, Thoughtfulness, Engagement, and Diversity—or as I think of it, how I ACTED.

When I first shared these with my team, a seasoned veteran on the team—someone a older than me that had worked at that company for several years before I joined—responded with surprise. She said, “Wow, no one has ever talked with us like that before.” By being direct about what mattered, I was able to model the way for a team that had been starved for clarity. They stayed, they engaged, and we built a culture of trust. That is the true nearly impossible project: bringing your whole self to work so that others have the courage to do the same.

A Fearless Path for the New Year

As someone who runs toward problems instead of away from them, these stories capture my personal ethos. It explains why I’ve taken the roles I have and why I’m currently working on the forefront of AI in the media business. We are using new technology to reinvent how we do work in an industry that is itself adapting to rapidly changing consumer trends.

As we wrap up this year, the takeaway is that we must be fearless while remaining humble in our learning. We must be willing to be “frequently wrong” as we explore, but “never in doubt” when we have set our intention to act.

The most fulfilling ventures will often be the ones that seem impossible at the start. But when we are motivated, inspired, and grounded in the actual practice of the work, we can accomplish things no one ever thought were possible.

How to Do Good by Doing Better and Up Your Impact, One Act at a Time:

Reclaim Your Tools: This week, dive back into a technical or tactical part of your job you’ve “delegated away.” Whether it’s drafting a prompt, running a query, or sketching a design, stay connected to the craft.

Embrace the “Wrong” Answer: Reflect on a long-held belief or “fact” in your industry that might be due for a rethink. Approach it with a beginner’s mind.

Model the Way: Identify one behavior you want to see in your team—whether it’s curiosity, directness, or hard work—and make sure you are the one setting the pace this week.

My wish for you—and for all of us—is a 2026 filled with “nearly impossible” projects and the conviction to see them through.

Related Reading

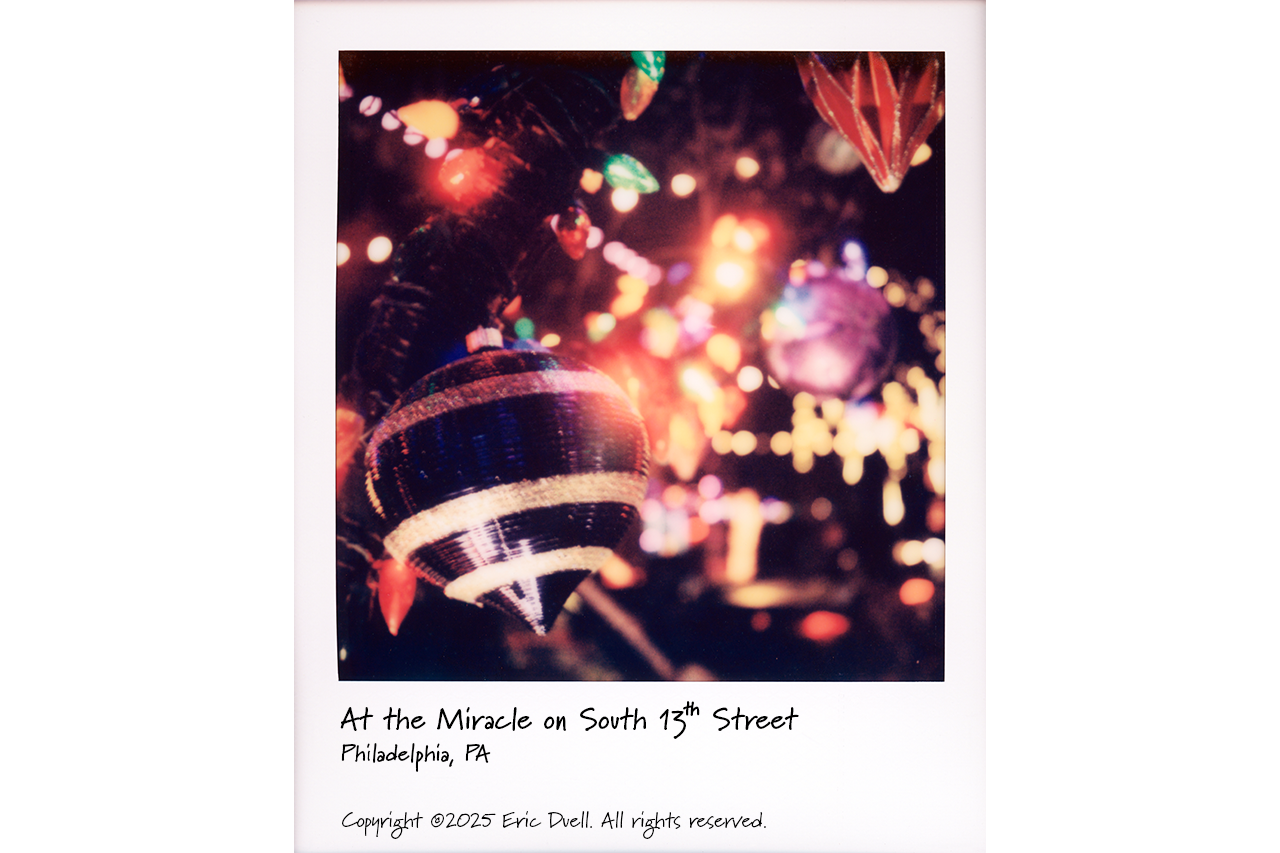

Photo Bonus

Sometimes you just gotta head out there to see what’s awaiting you…and that’s where I discovered this perfect shot to capture the glow and warmth of the holiday season, at the Miracle on South 13th Street holiday light display here in Philadelphia. This photo and another from the same series were recently featured on the Instagram feeds of The Instant Film Project and Lomography (last shot in the series, with the candy canes on the steps). I wish you and yours all the best!